Does God have a body? That’s the question at the center of biblical scholar Francesca Stavrakopoulou’s entertaining new book, God: An Anatomy.

The traditional answer among Jewish and Christian theologians has been no. Apart from the Christian belief that God became incarnate in Christ, God has been viewed as an abstraction, utterly transcendent, surpassing bodily existence.

But Stavrakopoulou argues that Judaism and Christianity are “post-biblical religions” whose disembodied deity is at odds with the God of the Bible. The biblical god, Yahweh, appears in “startlingly anthropomorphic ways.” Like the Babylonian deity Marduk or the Greek god Zeus, he had arms, hands, legs, feet, and even genitals. “He was a god,” Stavrakopoulou writes, “who fell in love and into fights; a god who squabbled with his worshippers and grappled with his enemies; a god who made friends, raised children, took wives and had sex.”

Over time, theologians grew embarrassed with this god. Influenced by the Platonic notion of the immateriality of the divine, they imagined a more rarified deity, exemplified in the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, where Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are one incorporeal “substance.”

Yet one major Christian tradition resists this abstract, disembodied deity. Though it’s beyond the scope of Stavrakopoulou’s book, Mormonism is distinctive for its embrace of anthropomorphism. As Terryl Givens shows in his definitive account of Mormon theology, early Latter-day Saints rebelled against the idea that God, to quote the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles (1563), is “without body, parts, or passions.”

As Givens points out, the Mormon prophet and founder Joseph Smith emended Genesis 5:1-2 to stress God’s embodiment (Smith’s addition in italics): “In the day that God created man, in the likeness of God made he him; in the image of his own body, male and female, created he them.” In a later revelation, Smith was more explicit: “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s” (Doctrine & Covenants 130:22).

God’s body also appears in Latter-day Saint worship. The first hymn in the LDS Church’s present hymnal (1985) is “The Morning Breaks” by Mormon Apostle Parley P. Pratt. The fourth stanza reads: “Jehovah speaks! Let earth give ear, / And Gentile nations turn and live. / His mighty arm is making bare, / His mighty arm is making bare, / His cov’nant people to receive.” The image of God’s mighty arm is a reference to 3 Nephi 16:20 (itself a quotation of Isaiah 52:10): “The Lord hath made bare his holy arm in the eyes of all the nations; and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of God.”

Stavrakopoulou alludes to the same passage from Isaiah 52, noting that in the aftermath of the Babylonian exile, Yahweh “flexes his muscular arm like a bodybuilder as he accompanies his repatriated exiles in triumphal procession back to Jerusalem.”

Does such imagery debase God? Many modern thinkers thought so. Charles W. Eliot, the president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, once predicted that the “religion of the future will not perpetuate the Hebrew anthropomorphic representations of God,” which he dismissed as “archaic and crude.”

Later in the twentieth century, feminist theologians such as Mary Daly raised a different concern, that the traditional masculine imagery for God risks absolutizing a divine gender. “Sophisticated thinkers, of course, have never intellectually identified God with a Superfather in heaven,” Daly explained. But the problem with male imagery, including the constant use of male pronouns, is that it unconsciously shapes our thought, even if rationally we insist that God is genderless.

I take Daly’s objection seriously. As a historian of American religion, however, I’m equally intrigued by Mormonism’s reversion to a more Hebraic deity. Mormonism’s embodied Father becomes even more fascinating when seen alongside his spouse, the Heavenly Mother (analogous to Yahweh’s consort Asherah), who is less well-defined in official LDS theology but nevertheless a vital part of the tradition.

Whatever one thinks of Latter-day Saint belief, it partakes of the primal human—and biblical—longing to make God tangible. “Throughout the Hebrew Bible,” Stavrakopoulou writes, “it is the intensity of a face-to-face encounter with God that worshippers most desire.” Psalm 105:4 puts it poetically: “Seek the Lord [Yahweh], and his strength; seek his face evermore.”

I can’t belittle this desire, especially in a day when war is again erupting, when nations are crying out for deliverance. In such a time, the biblical hope that Yahweh will bare his mighty arm does not seem so archaic, so primitive, after all.

© 2022 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

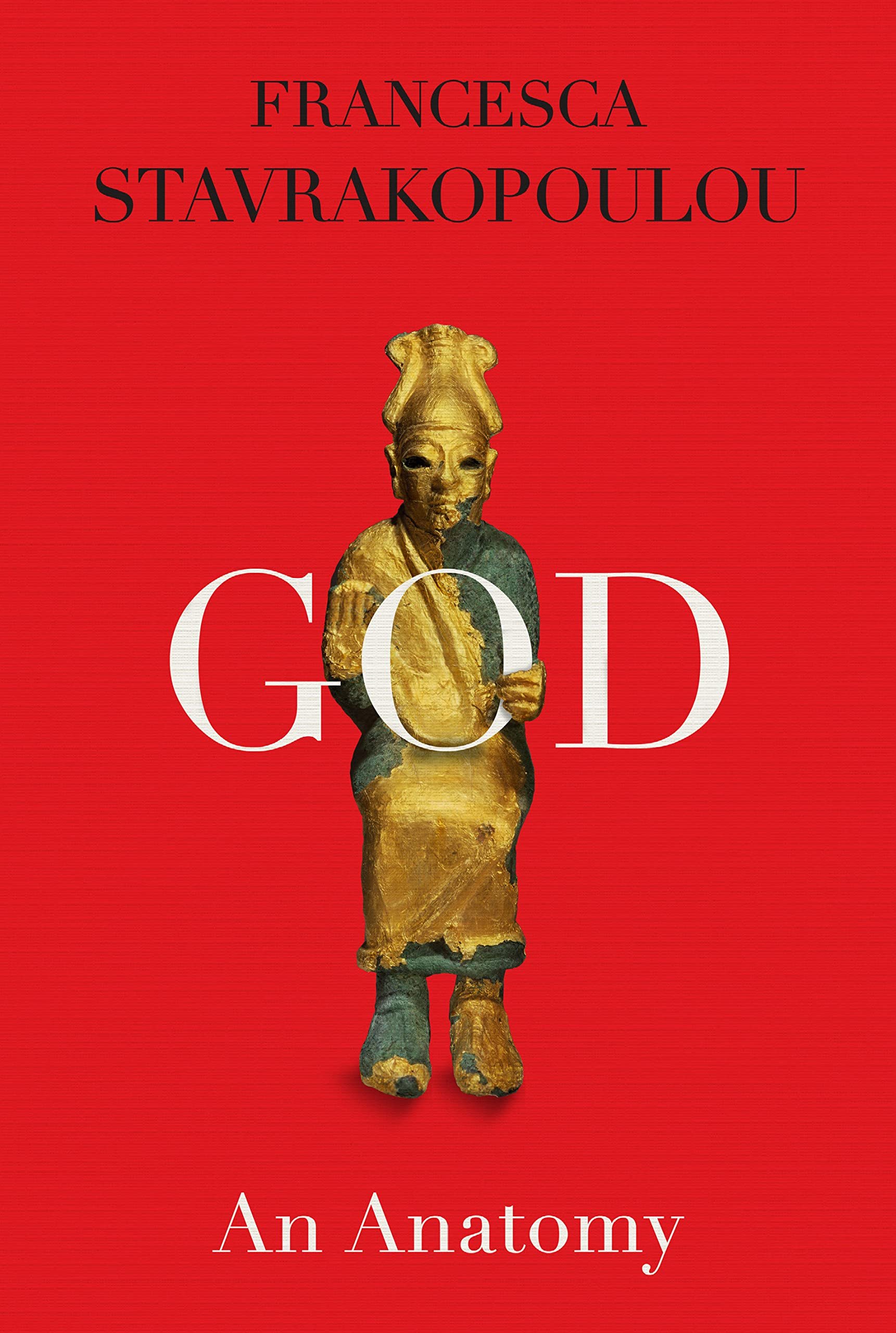

Illustration credits: God: An Anatomy (Knopf, 2022)

Asherah figurine: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bibliographical Note

Francesca Stavrakopoulou, God: An Anatomy (New York: Knopf, 2022), 9, 11, 18, 258, 311, 420-21; Terryl L. Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 89, 94-95, 106-11; Charles W. Eliot, The Religion of the Future (Boston: John W. Luce, 1909), 16-17; Mary Daly, Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, rev. ed. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1985), 17-18. On recent feminist appropriations of Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother, see Joanna Brooks, Rachel Hunt Steenblik, and Hannah Wheelwright, Mormon Feminism: Essential Writings (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).