Last week brought the beginning of a new semester and a bumper crop of 36 students to my biennial course “Religion, Death, and Dying.”

It’s a sobering subject, especially amid a pandemic. But as I tell the students, even as we confront death’s reality, we must save room for humor too.

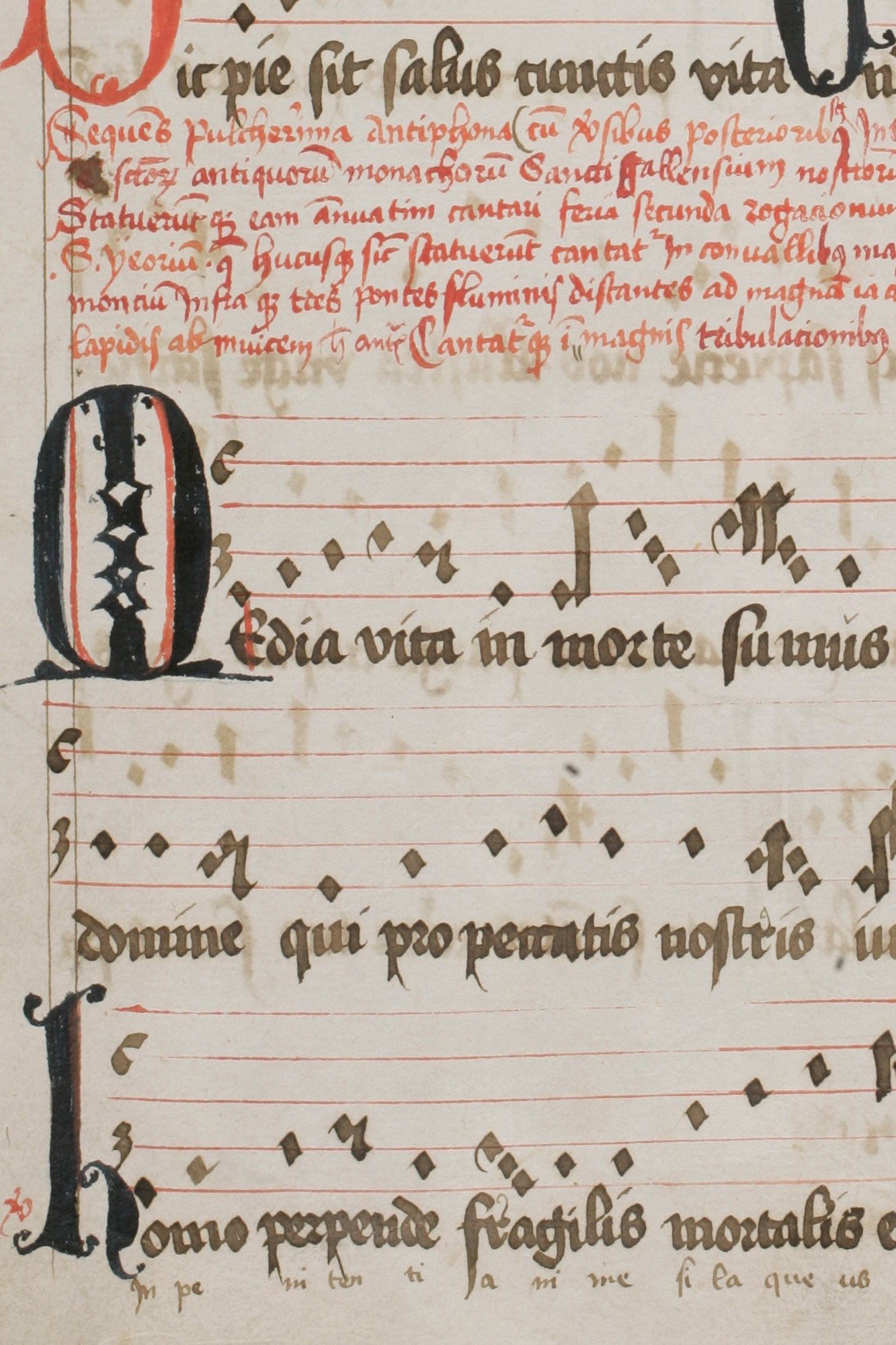

We begin by acknowledging the inevitability of death. In the course description on the syllabus, I quote from the burial rite in the Book of Common Prayer: “In the midst of life we are in death.” It’s the opening line of an anthem once attributed to Notker the Stammerer (d. 912), a Benedictine monk of the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland. According to legend, Notker composed the anthem, Media vita in morte sumus, while watching the construction of a bridge over a chasm. Realizing the danger that threatened the workers, Notker wrote:

In the midst of life we are in death;

of whom may we seek for succor,

but of thee, O Lord,

who for our sins art justly displeased?Yet, O Lord God most holy, O Lord most mighty,

O holy and most merciful Savior,

deliver us not into the bitter pains of eternal death.Thou knowest, Lord, the secrets of our hearts;

shut not thy merciful ears to our prayer;

but spare us, Lord most holy, O God most mighty,

O holy and merciful Savior,

thou most worthy Judge eternal.

Suffer us not, at our last hour,

through any pains of death, to fall from thee.

That the story about Notker is likely untrue doesn’t detract from the pathos of the text, which in its Latin original became part of the Lenten liturgy in the Sarum rite, the missal used in medieval England. Martin Luther translated the anthem for the German burial service, and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer integrated an English version into the Book of Common Prayer. According to liturgist Massey Shepherd, Media vita represents a striking example of the medieval “sense of awe and dread in the presence of death.”

Particularly powerful is the musical setting of Media vita by John Sheppard (d. 1558), who may have composed it during the devastating influenza epidemic of 1557. In this monumental choral work, the agony of loss is palpable. (I recommend the recording by Stile Antico.)

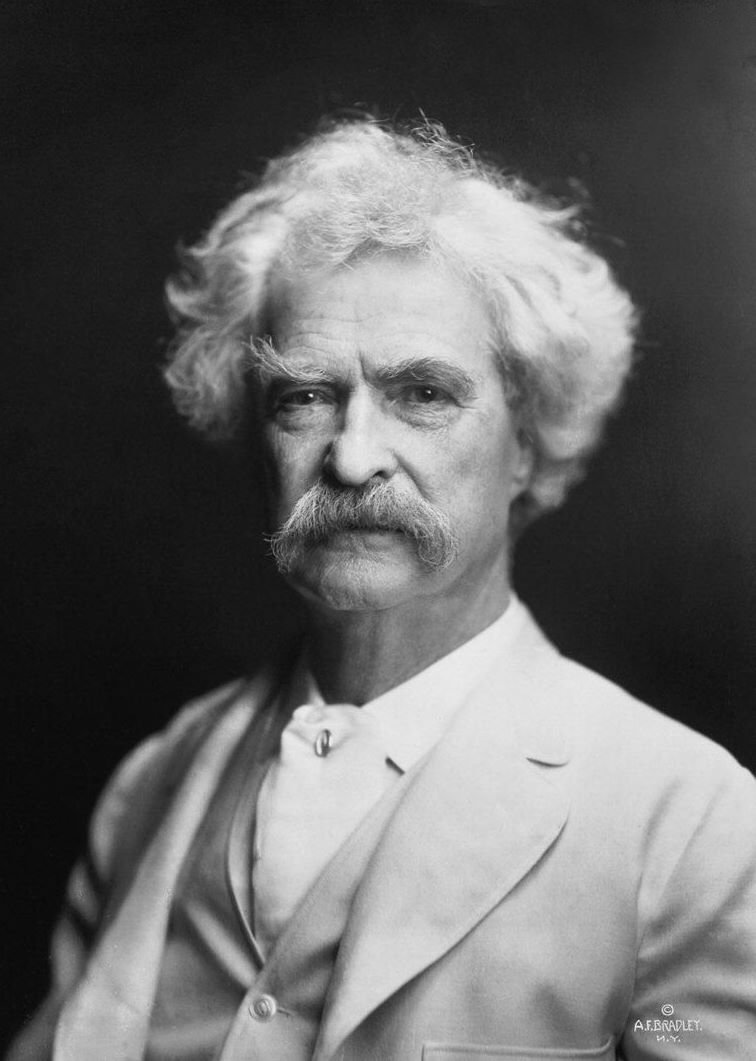

One American who knew the agony of loss was Mark Twain. In the last years of his life, he grew despondent following the deaths of his 24-year-old daughter Susy from spinal meningitis, his 58-year-old wife Livy from heart failure, and his 29-year-old daughter Jean from drowning after suffering a seizure in the bathtub.

To Twain, the words of Media vita would have rung all too true. We’re already in the process of dying. Death comes for us all, sometimes when we’re least prepared. The untimely deaths of his wife and daughters fueled Twain’s own religious skepticism, which left him increasingly comfortless as he approached the end of his own life.

But Twain also left us plenty of gallows humor about death. I quote one of his memorable lines on my syllabus: “I think we never become really and genuinely our entire and honest selves until we are dead—and not then until we have been dead years and years. People ought to start dead, and then they would be honest so much earlier.”

Twain’s mordant wit expresses an important truth: in thinking seriously about death, we become more honest with ourselves and others. That’s the premise of my course. While part of the goal is cultural competency—learning how different religions approach death—the deeper purpose is existential. By contemplating death in the midst of life (media vita), we gain wisdom for living.

© 2022 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

Illustration credits:

Media vita, Codex Sangallensis 546 (1513), Stiftsbibliothek, St. Gallen

Mark Twain in 1907 by A. F. Bradley

Bibliographical Note

The translation of Media vita in morte sumus quoted above is from the 1979 American Book of Common Prayer, Burial of the Dead, Rite One, p. 484. On the Notker legend, see Massey Hamilton Shepherd, Jr.,The Oxford American Prayer Book Commentary (New York: Oxford University Press, 1950), 332-33; Marion J. Hatchett, Commentary on the American Prayer Book (San Francisco, Harper, 1995), 484-85; and David Hiley, “Notker,” Grove Music Online (2001). On Mark Twain, see Peter J. Thuesen, “American Christians and the Emptiness of Death,” Church History 85 (2016): 360-64. Twain quotation from Mark Twain in Eruption: Hitherto Unpublished Pages about Men and Events, ed. Bernard DeVoto (New York: Harper, 1940), 203.