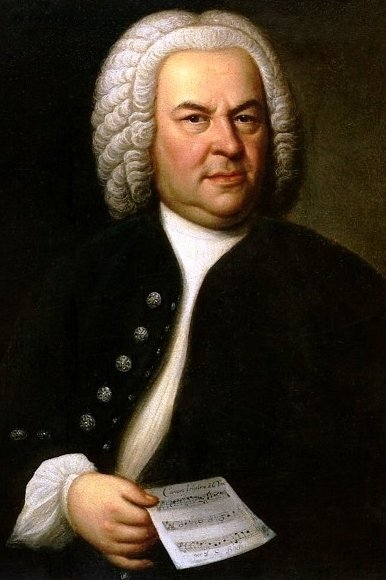

The New York Times recently gave music lovers a treat when the newspaper added a playlist of selections from Johann Sebastian Bach to its “5 Minutes” series. (The series asks experts what piece they would recommend to make someone love a composer after just five minutes of listening.)

Bach is my favorite composer, so I was pleased to see some of my own top choices on the list, including his early funeral cantata known as the Actus tragicus, BWV 106 (recommended by John Eliot Gardiner) and his organ Fugue in E-flat major, “St. Anne,” BWV 552 (recommended by David Allen).

But as one who loves Bach’s organ works above all, I have another favorite of this genre: the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 538, nicknamed the “Dorian.” (This is not to be confused with his more famous D minor Toccata and Fugue, BWV 565, which so often appears among Bach’s greatest hits.)

The Netherlands Bach Society has posted free on the web an exquisite recording of the “Dorian,” performed by Leo van Doeselaar on the Baroque-era Christian Müller organ of the Walloon Church in Amsterdam. I love watching Van Doeselaar’s feet work the pedals and his whole body shake as the fugue nears its contrapuntal climax.

In his new biography of Bach, David Schulenberg calls the “Dorian” “one of Bach’s most austere, uncompromising instrumental compositions.” The fugue is structured around canon, or precise imitation, unlike many fugues where the imitation is looser. “There are no fewer than fifteen canonic passages over the course of the fugue; these increase in complexity and level of dissonance as the piece progresses,” Schulenberg writes.

Reading Schulenberg takes me back to my undergraduate days at UNC-Chapel Hill when he blew my mind with his “Bach and Handel” course. As I learned then, it takes a highly trained ear to appreciate all the nuances of Bach’s counterpoint. Even now, after decades of listening to Bach’s organ works, I’m no expert.

What do I hear in the “Dorian” that I find so arresting? It’s a question that fascinates me about all music, especially purely instrumental works like Bach’s organ repertoire. Why does music resonate? In his book Resonance, the sociologist Hartmut Rosa writes that music seems to open up a realm of experience inaccessible to other languages. Music constitutes an “irreducible aesthetic excess,” a wealth of meaning that defies conventional analysis.

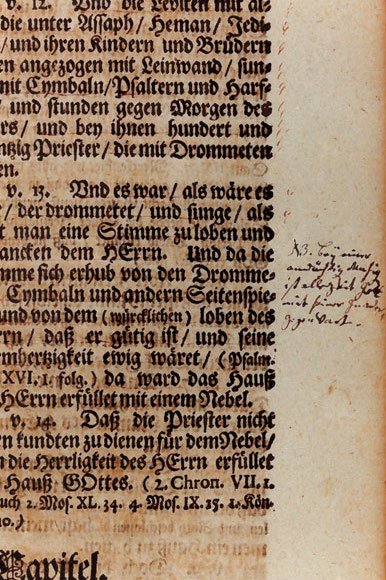

For Bach, the pious Lutheran, music conveyed God’s grace. He jotted a revealing comment to this effect in the margin of his Calov Bible (page pictured above), an annotated edition by the Lutheran dogmatician Abraham Calovius. The context is 2 Chronicles 5:13–6:1, which describes the dedication of Solomon’s Temple. In the New Jewish Publication Society translation, the passage reads:

The trumpeters and the singers joined in unison to praise and extol the Lord; and as the sound of the trumpets, cymbals, and other musical instruments, and the praise of the Lord, “For He is good, for His steadfast love is eternal,” grew louder, the House, the House of the Lord, was filled with a cloud. The priests could not stay and perform the service because of the cloud, for the glory of the Lord filled the House of God. Then Solomon declared: “The Lord has chosen to abide in a thick cloud.”

Bach wrote in the margin: “NB. With devotional music, God is always present in his grace.”

To me, the cloud is as potent a metaphor as the music itself. Like the divine presence hidden in the cloud, music conveys meaning that transcends any rational description. Who is to say what the “Dorian,” or any great composition, finally “means”? All I know is that it speaks to me like the proverbial cloud of unknowing; I feel its power in a mystical way.

© 2021 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

Bibliographical Note

Quotations from David Schulenberg, Bach (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 111. Quotation from Hartmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, trans. James C. Wagner (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 94. Bach’s Calov Bible is held by Concordia Theological Seminary, St. Louis, which is the source of the photo above. On Bach’s handwritten notation on 2 Chronicles 5, see the comment in Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000), 339.