Latter-day Saints are once again embroiled in controversy over Mormonism’s doctrine of the Heavenly Mother, divine spouse of the Heavenly Father.

At the recent General Conference (April 2-3, 2022), apostle Dale G. Renlund, in an apparent effort to rein in feminist theology, admonished Latter-day Saints not to pray to Heavenly Mother, even though the church teaches that all humans “are beloved spirit children of heavenly parents, a Heavenly Father and a Heavenly Mother” (Gospel Topics Essays).

Renlund’s address followed other recent comments in which he contrasted the “speculation” about a Heavenly Mother with the scriptural revelations attesting to a Heavenly Father.

Ironically, Renlund’s argument—that the Heavenly Mother is mere speculation—was later echoed by an opponent of Mormon theology, R. Albert Mohler, Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and a leading voice of conservative evangelical Protestantism.

In his daily radio commentary, Mohler discussed the LDS controversy and decried the “obviously feminist agenda” behind calls to pray to Heavenly Mother. “Remember, evangelical Christians,” he told his listeners, “there is no Heavenly Mother. There is no consort to God the Father the Almighty. This is something that came by the invention of a late adolescent male in upstate New York in the 19th century.”

Mohler concluded that there is “no more graphic example” of the distinction between “historic biblical Christianity” and Mormon theology than the doctrine of the Heavenly Mother.

Mohler is wrong that Joseph Smith invented the notion that God the Father has a consort. In fact, the idea is present in scripture. As the archaeologist and biblical scholar William G. Dever has noted, the word asherah occurs more than 40 times in the Bible, usually in reference to a cultic, tree-like object dedicated to Asherah, the Canaanite mother goddess, who was associated with sacred trees.

Many ancient Israelites apparently regarded Asherah as a consort to Yahweh. Archaeological discoveries from the 8th century BCE contain the inscription “Yahweh and his Asherah.” This popular belief alarmed the biblical writers, who like today’s conservatives (whether Mormon or evangelical), tried to stamp out the mother goddess’s cult. Deuteronomy 16:21 expressly forbids erecting an asherah next to the altar of Yahweh. In 2 Kings 23:15, Josiah burns an asherah that had been placed next to Yahweh’s altar at Bethel.

Yet readers of the King James Bible—including the Prophet Joseph Smith—would have been unaware of the full significance of these references because in that translation asherah or asherim always appear veiled in phrases like “groves” or “every high hill and green tree.” Dever calls this erasure “Asherah Abscondita.”

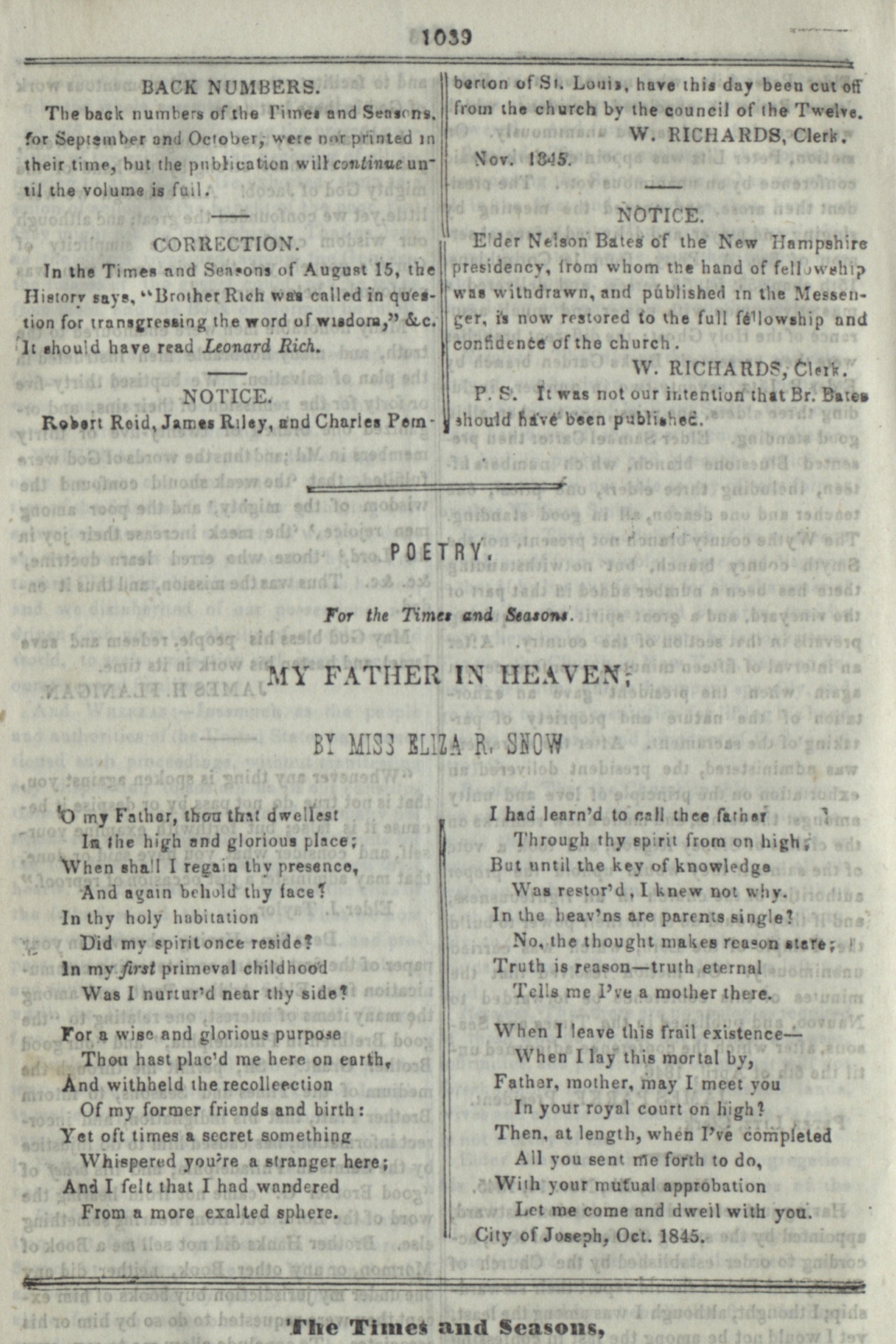

If Joseph Smith was unaware of the biblical Asherah, then Mohler may be partly right that the Heavenly Mother originated, at least for Latter-day Saints, in his own speculation. Smith’s role is a debated point in LDS history. The first clear reference to the Heavenly Mother comes from a hymn by Eliza R. Snow, one of Smith’s wives. But the church’s sixth president, Joseph Fielding Smith, Sr., claimed that God first revealed the Heavenly Mother to Joseph Smith, who revealed it to Snow.

Still, even if the Heavenly Mother originated in Smith’s (or Snow’s) speculation, I fail to see how that diminishes the power of the idea. What is scripture, after all, but canonized speculation? Even if we regard the Bible or the Book of Mormon as divine revelation, they are still speculative in that they represent humans’ grasping for God in their own limited language.

Eliza Snow’s hymn, “O My Father,” (no. 292 in the current LDS hymnal), speculates its way to a Heavenly Mother: “In the heav’ns are parents single? / No, the thought makes reason stare! / Truth is reason; truth eternal / Tells me I’ve a mother there.”

In the recent General Conference, Renlund cautioned against giving reason free rein: “Reason cannot replace revelation. Speculation will not lead to greater spiritual knowledge.”

But the line separating reason and revelation, or speculation and knowledge, is rarely clear within religious traditions. Doctrine is language that operates by its own internal logic. And it arises from human yearnings on this side of the veil.

Those yearnings have led people to a Heavenly Mother since before the biblical Israelites. And reason tells me that no General Conference address will stop Latter-day Saints from seeking her.

© 2022 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

Bibliographical Note

William G. Dever, Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2005), 102, 163, 209. On Asherah, see also Susan Ackerman, “The Queen Mother and the Cult in Ancient Israel,” Journal of Biblical Literature 112 (1993): 385-401; and Francesca Stavrakopoulou, God: An Anatomy (New York: Knopf, 2022), 149-52. On Eliza Snow and Joseph Smith, see Linda P. Wilcox, “The Mormon Concept of a Mother in Heaven,” in Sisters in Spirit: Mormon Women in Historical and Cultural Perspective, ed. Maureen Ursenbach Beecher and Lavina Fielding Anderson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 64-77. See also the overview of the Heavenly Mother doctrine in Terryl L. Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 106-11.

Illustration Credits: Eliza R. Snow, c. 1852, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; Eliza Smith’s hymn as printed in Times and Seasons, November 15, 1845, Digital Collections, Brigham Young University Library