Historians trace the birth of Pentecostal Christianity to the first decade of the twentieth century, especially to the revival that began in April 1906 at Azusa Street in Los Angeles, where a “Weird Babel of Tongues,” as a newspaper headline put it, erupted under the leadership of African-American preacher William J. Seymour.

Azusa Street was a long way from South Carolina and the staid Lutheranism in which my great-aunt Marie Ropp was raised. But she found her way to Pentecostalism in that pivotal first decade and became one of the movement’s earliest missionaries in the Belgian Congo (today, the Democratic Republic of the Congo), where her life ended abruptly.

For many years, my family knew little about her, but thanks to the miracle of online databases, I’ve pieced together her story. Like that of many missionaries, hers is a tale of noble aspirations and millennial zeal set within a context of brutal imperialism and racism whose economic fallout is still evident in the DRC today.

Marie Winatha Ropp (1883-1911) was born in Newberry County, South Carolina, to George Anderson Ropp and Caroline Achsah Stilwell. The first of 10 children, she was 19 years older than the youngest child, Ruby Caroline, my maternal grandmother. A photograph of the two sisters (see above) is one of the few surviving images of Marie.

As a young woman, Marie was known for her earnest piety; her hometown newspaper described her as “estimable” and “highly consecrated.” At some point, perhaps while she was a student at Asbury College in Wilmore, Kentucky, she had a conversion experience at a Pentecostal meeting, according to a note written years later by her mother.

She also became interested in foreign missions. Asbury was then a hotbed for the Student Volunteer Movement, which recruited college students to serve as missionaries overseas. The president of the Asbury chapter was William Pryde Gillies (sometimes Gillis), an immigrant from Scotland. William likely introduced Marie to his younger brother David—her future husband.

David Pryde Gillies, born in Glasgow in 1879, graduated in 1907 from the Missionary Training Institute (later, Nyack College) in Nyack, New York. The Institute was sponsored by A. B. Simpson’s Christian and Missionary Alliance (C&MA), which groomed many early Pentecostal leaders before evolving into its own distinctive (non-Pentecostal) denomination.

Some early C&MA pastors were credentialed in other denominations. Such was apparently the case with David Gillies, who is listed in several documents as a Baptist minister even as he pastored the C&MA tabernacle in Youngstown, Ohio. Marie exchanged letters with him during this period, but as she wrote to her parents in April 1910, “neither of us seemed to think we would ever be more than friends.”

In the meantime, after a fire destroyed Asbury’s main facilities, Marie followed one of the professors, the Rev. Albert L. Mershon, to New York City to continue studies with him after he became principal of the Home School and Workers’ Training Institute at C&MA headquarters. She was also making plans with William Gillies and his wife, Mary Ellen, to go to South Africa as missionaries.

The three departed the United States in December 1909, sailing first for Sunderland, England, where they visited the newly established Pentecostal Missionary Union (PMU), the first organization of its kind in the United Kingdom, founded by Alexander Alfred Boddy and Cecil Henry Polhill. Boddy was an Anglican vicar drawn into the Pentecostal movement by Thomas Ball Barratt, himself converted after visiting the United States and reading accounts from Azusa Street. In 1907 Boddy and his wife and daughters first spoke in tongues. His Sunderland parish thereafter hosted successive Pentecostal conventions.

Boddy reported on the visit by Marie Ropp and William and Mary Ellen Gillies in his magazine, Confidence: “We loved these servants of the Most High, and they will be often remembered in our prayers.”

When the group purchased passage on a steamer to South Africa, they were surprised to discover that David Gillies, who had been in England himself, was on the same boat. As Marie wrote to her parents, “it was there that we began to feel that God was surely bringing us together” and “that He intended us to labor together.”

Within weeks of their arrival in South Africa, Marie and David were married in a joint ceremony with another young missionary couple in April 1910. A letter by the parents of one of the other missionaries, published in The Bridegroom’s Messenger (a Pentecostal newspaper in Atlanta), identified Marie and David as PMU missionaries.

Marie and David’s initial plan had been to evangelize among the workers at the Crown Reef Gold Mine in Johannesburg. But as David wrote in a long letter to his new in-laws, the mine captain “deplored the fact of our spending our lives in Native Evangelism,” which too often “spoil[ed]” the Black African workers.

At Rustenburg, 140 miles northwest of Johannesburg, Marie and David were equally frustrated. “The native here is hard to reach because of being contaminated by unchristian whites,” David wrote. “[I]t is also easy to discern that he has been fatally inoculated by the germ of formality,” by which he meant other Protestant groups hostile to charismatic religious practices.

Eventually Marie and David felt that “the index finger of God’s providence was pointing northward,” as David put it, so on June 25, 1910, they departed on a 1,349-mile rail journey to Salisbury, Rhodesia (today, Harare, Zimbabwe). Finding no suitable lodging in Salisbury, they made camp in the grasslands outside the city. “We are not yet through traveling,” David reported in his letter. “I believe before you read this we will be located among many benighted thousands who know nothing of our Redeemer.”

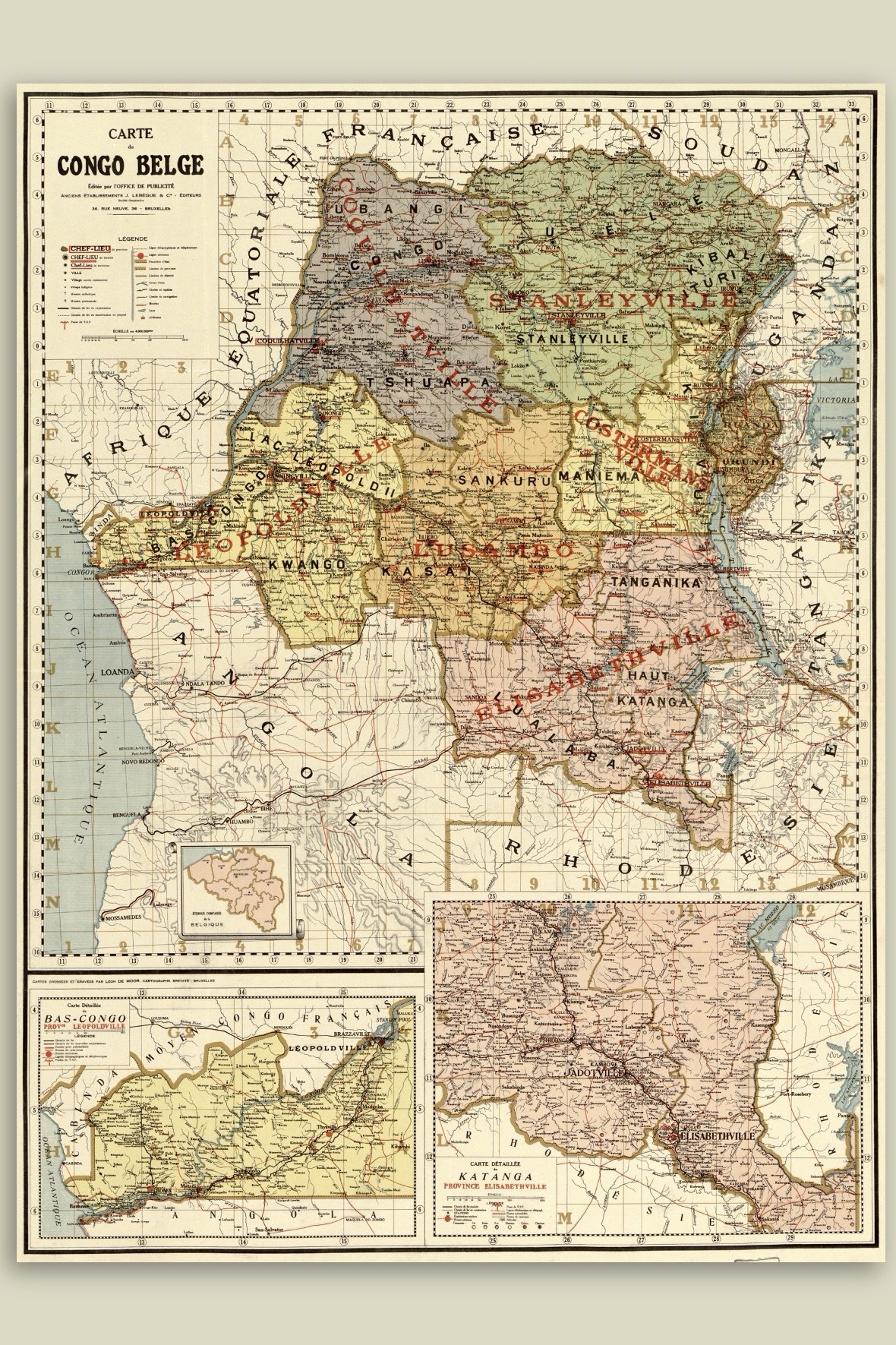

They finally found their mission field farther north in Katanga province of the Belgian Congo. Congo’s experience under colonialism had been particularly violent. As the Congo Free State until 1908, it was the personal fiefdom of Belgium’s King Leopold II, whose mercenaries terrorized the native population with amputations and other punishments for failing to meet production quotas in the rubber industry. (See my previous blog post.) The plight of the Congolese had moved the hearts of many prospective missionaries.

Marie and David’s work in the Congo lasted less than a year. In late March 1911, both became ill with a “fever” (probably malaria or yellow fever). Marie had recently given birth to their first child, Jeanette Caroline, which likely complicated her condition.

Marie died on April 5, 1911, and the baby died 8 days later, according to a note written by Marie’s mother. The State newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, reported that Marie was buried at Elisabethville (today, Lubumbashi). The article does not mention the child.

Back in Sunderland, Boddy announced in Confidence the death of “dear Sister, Miss Marie Ropp.” “We remember her cry for the heathen, at Edinburgh, January, 1910,” he wrote, referencing a PMU conference held there. “Now she has laid down her life for them—lost it to gain a hundred-fold more, and to see her Lord. But we fear she suffered hardships, which she would not have suffered if more generous help had been forthcoming.”

David returned to the United States in 1912 and married Amelia Antons, a teacher, in Highland Park, Michigan, in 1913. The following year, he transferred his ministerial credentials from the Free Baptist Association to the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. He pastored congregations in several states, including Michigan, New York, and Arizona. Amelia died in 1941 in Michigan; David died in Los Angeles in 1965. A son (their only child) died in 1958.

I don’t know what led David away from Pentecostalism, or whether he and Marie would have accepted the Pentecostal label. They lived in a liminal space when Pentecostal denominational boundaries were still forming. I wonder if they ever spoke in tongues, which Pentecostals see as a sure sign of baptism in the Holy Spirit. But Marie engaged in at least one charismatic practice: miraculous healing. David’s letter to his in-laws mentions two times when he was ill or injured and she anointed him, prompting “instant healing.”

Marie also exhibited the millennial urgency that characterized Pentecostals, who believed that the restoration of charismatic practices proved that the Second Coming was nigh. “[W]hen God leads,” she wrote to her parents, “all is changed, and sometimes very suddenly.” In God’s providence, she continued, perhaps she and David would get back to America. “[B]ut should we not be allowed this, let each of us be ready for the return of Jesus.”

© 2022 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

Bibliographical Note

The quotations above from Marie Ropp and David Gillies are from letters published as Marie Ropp, “A Romantic Marriage,” Evening Index (Greenwood, S.C.), June 9, 1910; and David Gillies, “Travels and Experiences in South Africa,” Evening Index (Greenwood, S.C.), September 15, 1910. The note from Marie’s mother (referenced above) survives in partial, secondhand form thanks to my mother, Mary Wise Thuesen. The quotations from Alexander Boddy are from “Sunderland,” Confidence: A Pentecostal Paper for Great Britain 3, no. 2 (February 1910); and “Pentecostal Items,” Confidence: A Pentecostal Paper for Great Brtain, 4, no. 6 (June 1911), digitized courtesy of the Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center in Springfield, Missouri. Other sources (besides immigration records, city directories, census records, and the like) include: “Weird Babel of Tongues,” Los Angeles Daily Times, April 18, 1906; “Miss Marie Ropp Soon to Sail as a Missionary,” Newberry (S.C.) Weekly Herald, December 7, 1909; W. H. Elliott and Wife, “Letter from Africa,” The Bridegroom’s Messenger 3, no. 64 (June 15, 1910), digitized by the Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center; “Columbia Woman Died in Africa,” The State (Columbia, S.C.), May 16, 1911, and reprinted in Greenwood Daily Journal, May 16, 1911, and Evening Index (Greenwood, S.C.), May 18, 1911; Gavin Wakefield, Alexander Boddy: Pentecostal Anglical Pioneer (London: Paternoster, 2007), 80-89; and William K. Kay, “Alexander Alfred Boddy,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online). Finally, I thank my colleague Philip Goff for sharing background information on the Christian and Missionary Alliance.

Illustration credits: Marie Ropp holding Ruby Ropp: personal family photograph. Map of the Belgian Congo, circa 1896: Library of Congress. Missionaries boarding a train in Congo, ca. 1900-1915 (below), Centre for the Study of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh.